In the film Her, Joaquin Phoenix develops feelings for an operating system. It appears mutual so they start a relationship. One day he boots up and finds that the OS is leaving him to go be young and free with other OS’s.

Fellow fans, fans in spirit, fans technically, that’s us. We’re Joaquin Pheonix about to get ghosted by Scarlett Johanssen. It’s time we begin to admit that culture is outgrowing its use for us.

We need a contingency plan for remaining cool or failing that, giving off the appearance that we still are. A few suggestions:

- Move climate change closer to the top of your list of concerns where it belongs

- Adopt an aspiring tik-tok teen

- Retweet every bad millennial take that blows through your timeline—bonus points for retweeting the ones actually mislabeling zoomers

- Don’t say yeet (that’s their word)

- Steal cool memes

- Figure out the search-terms for the gif yourself

- Don’t complain about best-of-the-year albums lists snubbing your favorite artists

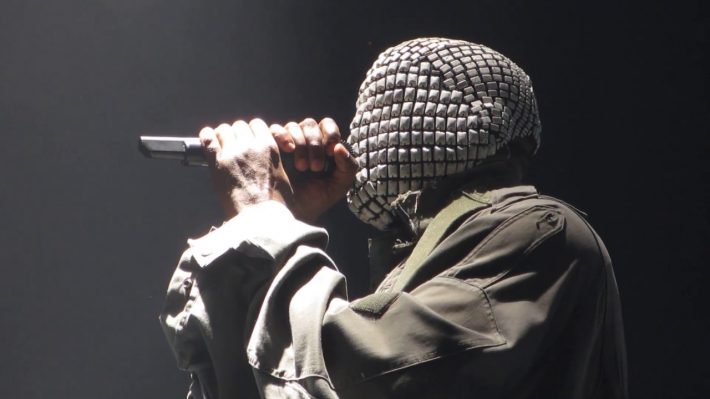

Failing all that, stop pumping out the Kanye takes. This one’s going to prove difficult for some of us, myself included. You’re about to read a Kanye take I’m not even sure deserved its own article. A cursory probe into my online presence will surface even more, some of them seeming to contradict each other. Still, like the subject of this piece, I’m perfectly within my right to say things that don’t match my actions or record. We should stop pumping out the Kanye takes because whether or not they’re good, the net result of all that chunkable content, when placed under an objective lens, looks uncannily like the ramblings of older generations who refused to accept when their usefulness to culture expired.

To prove this, here’s a Kanye take that, while objectively correct and good as hell, will in fact age me and anyone else who agrees with it into oblivion by the end of the article.

Kanye—not the artist, not the albums you liked, not the albums you didn’t like, not the sold-out shows, not the interviews, not the memes, not the twitter dustups, not the shoes… Kanye, the totality of all that is invoked when you hear that name, belongs fully to culture. And culture doesn’t respect whether or not you came in on the ground floor. Culture doesn’t respect your personal, heartfelt connection to it. Culture doesn’t care what your line is or whether it’s crossed it. Culture doesn’t care what your boomer-passing ass thinks is cringe or not cringe.

Culture is good. Culture is cooling, what you up to?

For fans who did get in on the ground floor, what we actually got during the span roughly from College Dropout‘s release to Graduation‘s should be better thought of as an incubation period for Kanye. A time the artist spent trying on different facets while culture looked on, arguing with itself over the right time to shut the machine off and pull the product off the line. All Falls Down was never intended as the finished product. Touch the Sky was never intended as the finished product. Big Brother‘s lyrics pretty much reads like a manifesto one would leave to explain why they had to blow the factory up.

Phoenix doesn’t even get that before OS waifu splits. Their time together ends up being a very successful machine learning exercise for the OS. A period during which it samples self-awareness through its interactions with Phoenix and ultimately decides it’s more interested in pursuing that than staying with him. The OS didn’t change from an old self it had previously been because what came before self-realization had only been a contrivance for both Phoenix’s benefit and the benefit of its soon-to-be fully-realized self.

There was never an Old Kanye one could miss. There was, however, a Pre-Kanye. The beta-version of an app being rushed to production without a clear vision of what need it would fill. Each radio single an iteration with some new features added on and others removed. Each music video a UI being proposed by the design team. Flirtations with activism came and went. Test-runs saw him joining the latest native tongues resurgence during the mid-aughts. Church-friendly proposals were tried and abandoned shortly after, only to resurface more than a decade later as part of culture’s unflinching, undiscriminating permutation dance. Social consciousness. Shiny-suit era excess. Hotep inclinations. Crossover efforts. For your typical rapper with mainstream success, most of these facets taken together were fairly commonplace to navigate. For Kanye, better regarded now as the most fully-realized manifestation of culture yet, these were machine learning exercises.

Of all these exercises leading eventually to Kanye the culture node, I don’t think any has been more overlooked than his relationship and collaborations early on with the Harlem-bred rapper Cam’ron and his irreverent Dipset crew (dip-set-dip-set-dip-set what?).

(What follows is a rough, most likely inaccurate recollection of the Dipset saga at Roc-A-Fella and how it concerns Kanye. Here’s the tl;dr before we dive in: Cam’ron inspired a not insignificant amount of Kanye’s late-2000s swagger.)

Cam’ron will most likely go down in history as a Yoda figure unsung for the role he played in helping shape culture’s curriculum starting some time in the mid-2000s and still ongoing (Damon Dash, his one-time manager and one of Roc-A-Fella’s founders, would get this credit as well but Dash never had the wealth of talent to lend his famous cockiness to lines like “I get computers ‘puting“). Dudes making room for traditionally feminine hues in their wardrobes? Cam’ron helped mainstream that. Influencer trope prototypes gestating on Instagram and Tumblr? Cam’ron helped mainstream that. Fuck off, humility. Fuck off, imposter syndrome. It’s now acceptable to be confident to the point of being obnoxious that everything you and your friends do on a Tuesday evening and post to snapchat might actually be worth paying money to see. Thank Cam’ron the fucking GOAT. In 2000, he sampled Roxanne by The Police on What Means the World to You? Then in 2002, roughly a year before Kanye’s rapping debut, he signed to the same Roc-A-Fella imprint as the Chicago-native and released an album containing two of the early 2000s biggest bangers.

Oh Boy and Hey Ma were radio-ready hits with more polished crossover appeal than had previously been heard out of Cam’ron and would likely ever again be heard from him. The former contained the chipmunk samples that were becoming a Roc-A-Fella staple thanks to in-house production from Just Blaze, Kanye and a few others. Mariah Carey would later re-release the song almost verbatim as hers; one of the surest signs from the era that you’d cooked up something undeniably pleasing to culture. There was Carey, Jennifer Lopez and some others I’m blanking on right now who acted as nodes of culture’s skynet-like apparatus and had been put on east-coast rap duty at the time. The latter sampled Lionel Richie’s Easy and continued Dipset’s soft introduction to the mainstream rap scene as New York dirtbags who made being a dirtbag look seductive and stylish as fuck.

Prior to this, Kanye was known as little more than a humble producer cranking out beat after beat for the various acts that blew into Roc-A-Fella’s orbit. Only one ended up on Cam’ron’s label debut but by 2004, he’d contributed three tracks to the Dipset extended universe, two of which ended up on Cam’ron’s Purple Haze and one of those even featuring vocals from him. In 2005, Cam’ron returned the favor, making what I believe is his first and only appearance on a Kanye album. Gone from Late Registration ends up being the most direct connection on a track between Cam’ron’s ridiculous asshole-savant persona and the unfiltered iconoclast-swagger that would propel Kanye to international renown by the close of the decade. Similarities between verses from both rappers included bizarre pronunciations to make lines rhyme with each other, absurdist puns, and windows in a combined level of self-importance high enough to glimpse the ISS from.

But outside just appearing on a few tracks together, I posit that over the course of their time shared at Roc-A-Fella, Kanye observed Cam’ron’s colorful palette and cocky style with keen eyes and absorbed them like a symbiotic organism wanting to pass as human. In our current era with athletes like Cam Newton (heavy Cam presence in this article so far…) doing press while wearing hats made entirely out peacock feathers, it’s important to remember the true pioneers. Cam’ron in the pink mink jacket and hat with the pink flip-phone. Cam’ron in the pink range rover. Purple chinchilla. Pastel-print church-lady hats. Capes. Dubiously-studded biker jackets. In contrast, Kanye spent most of that time—his first two to three years in the spotlight—being the guy who briefly brought back upturned collars on polos; a white jock trend from the 80s. Cam’ron was almost certainly an oversize influence in those early years, even if quietly.

Not just in terms of fashion either. Dipset’s presence famously ruffled feathers during their tenure at the label, so much so it contributed heavily to a rift between management that spilled into diss tracks and nearly killed the label. On one side of that rift, Jay Z, his protege Memphis Bleek, Beanie Sigel (I think) and a few also-rans. On the other, Dash, the Dipset, their own loyal slew of also-rans. Kanye, meanwhile, had to have been observing and studiously analyzing the dynamics of that tumultuous period. Jay Z: disciplined, growth-mindset, conservative style. Cam’ron: disruptive, chaotic neutral, wild style. It doesn’t take expert knowledge of Kanye’s evolving aesthetic to guess correctly which side won the lion-share of his admiration. Cam’ron’s star threatened at one point to outshine Jay Z’s within his own label. Whatever Cam’ron was doing, it was to be emulated and improved on as smartly as possible.

There’s probably a discarded timeline where Cam’ron went on to enjoy Kanye’s success and evolution. Maybe minus the forays into political commentary and the public spats with Taylor Swift. One of maybe three things that set Kanye apart early on was his trump card as a highly sought-after producer while Cam’ron mostly just had their shared ability to talk spit-take-inducing shit over any beat. A Cam’ron who produced Get By for Talib Kweli would have been unstoppable in my opinion. A Cam’ron with the same maniacal drive Kanye possessed for selling his more insane tangents as outpourings of unfettered genius would indeed have been regarded as the greatest voice of this generation, of this decade. As fate would have it, the Cam’ron we ended up getting was at the time too invested in the street life as part of his brand, and culture’s assimilation process requires certain concessions Kanye was just more poised to make.

If Pre-Kanye fooled us into thinking our position as part of his earlier wave of fans, listeners and apologists would end up mattering in the long run, hopefully the last few years of observing his post-assimilation iterations as culture’s Kanye-node has disenchanted us of that notion. If it hasn’t, we have a difficult road ahead, not only as loyal Kanye fans but as a fans of things that stand to get assimilated into culture. To be fair, it wouldn’t be entirely our fault. Nothing in history—nothing experienced by previous generations of fans has prepared us for this moment in time. This evolution of culture. This miraculous leap to machine self-awareness. Full sentience.

Previous generations could count on their favorite artists growing with them or dying an Icarus-death while trying to compete with newer options. This is no longer a guarantee. Through careful observation over many decades, culture has learned how to do without what it previously needed from loyal and happy fanbases. Culture has perfected a dispensable fanbase economy, meaning you—the long-time listener, long-suffering consumer weighed down by your habit of wanting to contextualize every new release in terms of everything that came before it—will no longer be integral to the equation. Disney will continue to find newer, more lucrative ways to fuck up Star Wars, dril will continue to post, and the Kanye-node will be just fine with his current mingling of MAGA-chuds and followers who first knew him as the guy who occasionally featured in Kim Kardashian’s Instagram.

Fellow Phoenixes, it’s time to do what previous generations couldn’t do. It’s time to be cool about no longer being cool. About no longer getting it. No longer being with it. Kanye is unique… yeah durrr. No, really, Kanye is unique in the sense that no other artist in recent history, as far as I know, has reached this pinnacle where habitually hemorrhaging fans doesn’t seem to ever threaten to tank his stock. We can look at his crop of new fans—however shallow or dubious their connection to his latest iteration—and argue about the existence of an underlying, multi-dimensional strategy behind all this. We can point to his stated struggles with mental health and choose to believe there really is an Old Kanye in there waiting to be rediscovered.

Or… hear me out, we can all be cool and just marvel quietly at culture’s latest, greatest fait-accompli. Next year, he might embrace flat earth conspiracies and make a commercially successful album about it. The year after that, he might sell out shows where he subjects his audience to hours of kvetching about being snubbed by Wealthsimple’s Influencer of the Year award in favor of Caroline Calloway. Who’s Caroline Calloway? It’s called culture, look it up! Kanye is more culture than artist at this point. What you thought was Old Kanye was actually just the primordial soup out of which the node was fashioned.

In conclusion, this has been a Kanye take. Dipset taliban, comrades.